It’s not often that I get mad at an article.

I can get angry at the content. In this day and age, it’s hard not to. I might even get outraged at the arguments they’re making. But I’m not angry at the article itself. I’m mad at what it’s saying, which is similar but not quite the same.

Today, I want to talk about one that left me furious.

Two weeks ago, I was browsing Quillette magazine, the epicenter of the Intellectual Dark Web. For the uninitiated, the I.D.W. is a haven for free thinkers, academics, and intellectuals who feel drowned out or left behind by the stifling PC discourse of our universities. This leads to some… uneven content. Its best is extraordinary. Its worst is abysmal.

When I came across Myles Weber’s article “When a Question of Science Brooks no Dissent”, I thought it was one of the good ones. Quillette writers have done amazing work critiquing the way we approach science today, and how it’s enabled things like the Replication Crisis. I was excited to read this. I was hyped.

Within two paragraphs, that hype turned to bitter disappointment, as I realized I was actually reading a perfect example of the Intellectual Dark Web at its worst.

Before I go over this piece, I encourage you to read it yourself so you know I’m not misrepresenting it. It looks long when you click it, but most of the page is comments.

Speaking Power to Truth

The thesis of Myles Weber’s piece is that there is an unjustifiable degree of climate alarmism in academia and on the left in general. He argues that we have shirked our duty to question the supposed consensus on the impact of global warming, and that many people who should know better have absolutely no idea how any of the science works. He thinks that his fellow professors “forget what our job is: Not to tell the students what to think, but rather to teach them how to think for themselves.”

That’s a serious accusation, especially since he levels it at earth-science professors and his department’s “self-proclaimed expert on climate matters”. And he describes some astounding anecdotes of the scientific illiteracy of his peers. He argues that their devotion to global warming alarmism shows a lack of intellectual curiosity. He argues that his fellow professors are passing that on to our students.

I can’t deny that educated professors should know the basics of how a greenhouse works, or that Minnesota isn’t in danger of an imminent glacial flood. But it’s worth looking at the examples he uses of the questions they should be asking. What does his idea of intellectual curiosity look like?

It turns out his idea looks nothing like actual scrutiny and a lot like tired conservative talking points. Every semester, he gives his students a series of questions on the climate, to demonstrate how much they need to learn to understand the issue of climate change. One example he gives is this: “Which greenhouse gas accounts for more of the tropospheric greenhouse effect than all the other greenhouse gases combined?”. The correct answer is “water vapor”.

This question seems innocuous, but it’s alluding to a common argument from conservative climate skeptics. It’s been debunked countless times, and we’ll go over it in more detail later, but it’s not good-natured skepticism. It’s propaganda.

Then there is this passage, where he argues that glacier melt is actually a good thing: “Under such conditions, rivers that swell every spring from snowpack melt would stay swollen into late summer from glacial melt. This is almost always a good thing while it lasts since the extra water helps people downstream irrigate their crops. (Moisture trapped in a mountain glacier is useless when it is not downright destructive.) This is yet one more reason why a warming climate is preferable to a cooling one. “

I’ve never seen the glacier variant before, but the argument that Global Warming is either a good thing or at least not bad is as common as the water-vapor myth, and is held even by the higher-ups in our current government.

Finally, there’s his choice of scientific issue to challenge. 97% of climate scientists agree with the scientific consensus on global warming, roughly as many as believe in evolution, and significantly more than believe vaccines are entirely safe. But he harangues his colleagues over the only one of those topics explicitly mentioned in the Republican party platform.

None of this should be surprising. Weber begins his piece, not by talking about scientific illiteracy, but by slamming Barack Obama for politicizing the Sandy Hook Massacre in 2012. Apparently, only 6 days after the atrocity, he was calling on foreign diplomats to honor the dead children by fighting Global Warming.

This non sequitur betrays his political agenda. A dispassionate skeptic would not spend nearly 500 words attacking a former president for politicizing a tragedy six years ago, in an article about academia. More than that, the vignette sounded off to me. Barack Obama was not a perfect president, but this did not sound like the man who broke down in tears in his response to the massacre.

I found a transcript of the remarks Weber was talking about. I encourage you to read them for yourself. They are eloquent, and insightful, a sermon on the fundamental experiences that we all share, on the capacity of tragedy to bring out the best in people, and how important it is that we remember that unifying force as we face the new, global challenges of the 21st century. I was moved.

He also barely mentioned global warming. It was only one of several examples of what we must unify to face, an afterthought in his remarks. Despite quoting extensively from the speech, nothing Weber said about it was true. He even got the date wrong. The Sandy Hook massacre happened on December 14th, 2012. He said Obama gave the remarks six days later, on the 20th. But according to the presidential archives, he gave that speech on the 19th. I’m not sure how he missed it, but it was probably an honest mistake.

In an interesting coincidence, the conservative magazine “The Washington Examiner” ran an article about the speech that implied Obama used it to make Sandy Hook about global warming, and that article came out on the 20th.

That’s Not How Science Works

The fact this piece is naively parroting Republican talking points doesn’t disprove its core thesis that we shouldn’t “brainlessly push climate-change alarmism.” Having a conservative agenda does not mean you’re wrong.

Being wrong does. Weber’s article taking his colleagues to task for their scientific illiteracy makes grievous errors every time he turns to scientific topics.

Take the water vapor question I mentioned earlier. The implication is that, because water vapor is more important in shaping our climate, that we don’t have that much to worry about from a small increase in carbon dioxide.

There are three issues with this line of reasoning. First, if there were no greenhouse effect at all, the earth’s average temperature would be about -18 degrees celsius, 33 degrees colder than it is today. Carbon dioxide and methane may only account for ten of those 33 degrees, but it turns out you don’t need to make the earth colder than summer on Mars to royally fuck up human civilization. Upping the carbon dioxide is enough on its own.

Second, more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere leads to more water vapor too. As carbon dioxide traps heat in our atmosphere and warms the planet, the oceans warm up, too. As they warm up, more water evaporates and becomes water vapor in the atmosphere. And as Weber presumably learned in the fourth-grade science class he assures us he didn’t sleep through, hot air holds more vapor than cold air.

Third, there is a special, highly technical process in climatology that regulates the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere and prevents it from causing catastrophic problems like carbon dioxide does, at least on its own. It can amplify already-existing warming trends, but it could never cause them, because this obscure process prevents it from building up in the atmosphere for long.

It’s called “rain”.

I wish this were the only time he mangled basic science to prove a point. But he seems incapable of getting anything right once he starts talking details. A few of his other errors include:

He confidently explains how increased glacial melt is a good thing, because it leads to a longer swell season downriver and helps people with their crops. Apparently, he hasn’t given any thought to what happens when there isn’t any more glacier to melt. Once it’s gone, there’s no more swell season downriver because there is no downriver: the water dries up as the glaciers disappear. Forget the flood danger, those farmers will lose their water supply.

In his conclusion, he describes a time he asked a climatologist to describe a foolproof experiment to prove humans cause global warming, if money weren’t an issue. The climatologist can’t think of one. When pressed for an example, Weber says such an experiment could involve the Antarctic ice shelf. He explains that West Antarctica and the Peninsula should be warming more slowly, since it’s surrounded by moderating ocean and has more water vapor, and East Antarctica should be warming the fastest, since it’s far from the oceans and cold enough to have little vapor. Since that’s not what’s happening, global warming seems dubious.

This is the opposite of the truth. We’ve known East Antarctica was more stable than the rest of the continent for decades, because of how the ice sheet interacts with bedrock. The bedrock is higher in the east, which means it’s harder for water to get underneath the ice sheet and accelerate the melting process. No such luck in West Antarctica. He got the expected outcome backwards.

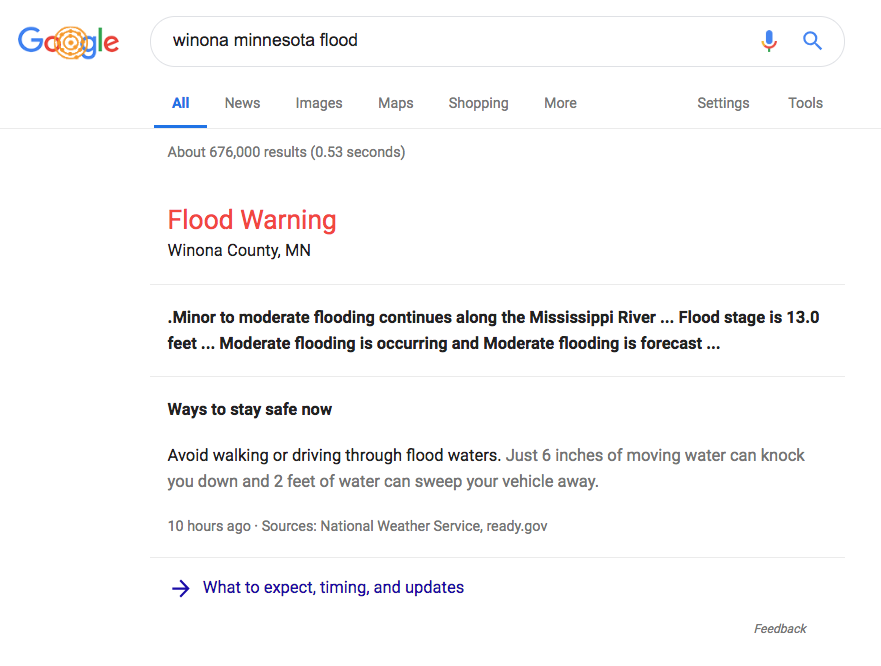

Early on, he mocks his colleague for believing their Minnesota town is threatened by climate-change related floods, due to glacial melt. While he’s correct that glacial melt isn’t the problem, global warming actually does mean greater flood risk in the Midwest. Warmer ocean temperatures lead to larger storms and longer storm seasons, creating both more snowmelt in winter and more water on top of that in spring. This has caused record floods along the Mississippi and its tributaries in 2011, 2014, 2016, and 2018.

It’s also why there’s an active flood warning in his county right now.

Weber not only betrays a lack of understanding of science and the impacts of global warming, he also displays little knowledge of the scientific method. It’s telling that, when asked to give an example of a hypothetical experiment to prove or disprove global warming, he gives one data point that is still subject to environmental factors. He seems fuzzy on the difference between “experiment” and “argument”.

Perhaps I should cut Myles Weber some slack. After all, he’s not a climatologist. He’s not a meteorologist. He’s not a scientist at all. He’s an English professor. His scientifically illiterate colleagues are English professors. I doubt any of them have taken a science class since the Reagan administration.

What sets him apart from his colleagues is another philosophical virtue: intellectual modesty. His colleagues know that they don’t know shit about climate science, so they blindly trust the countless researchers who do. Myles Weber, however, believes that he is more qualified to discuss the topic. He believes his skeptic’s mind gives him all the tools he needs to evaluate climate science, despite not referencing any scientific studies in his 3,000 word thinkpiece.

It’s unfortunate, because anyone who’s taught an undergraduate English course ought to know the dangers of confidently arguing something when all you’ve read about it is online summaries.

Play Stupid Games, Win Stupid Prizes

There is nothing remarkable about some dude writing an inane hot take about global warming. What struck me about this piece wasn’t the ignorance or the lack of self-awareness, but how petty it was about it.

It’s one thing to hypocritically complain about your colleagues in private. It’s another to do it publicly, on a major website at the heart of a political movement. He publicly shames his own coworkers for not remembering how greenhouses work, accuses them of being dumber than 10-year-olds, and does it all with the absolute certainty that his tragic misunderstanding of the sciences is correct.

In the words of one of the 21st century’s great philosophers, “Don’t be clowning a clown, you’ll wind up with a frown.” If Myles Weber wants our political discourse to be more petty, I am happy to oblige.

I’ve mentioned his strange choice of intro topic, a six-year-old speech by Barack Obama that had nothing to do with global warming, before. But it’s even worse when you realize he’s an English professor who ought to know better. The introductory paragraph of an essay is supposed to pull the reader in, explain your thesis, and provide a road map for how you’re supporting that thesis. Two paragraphs in, I’m not curious, just confused. I don’t know what he’s arguing, or how he’s gonna support it.

In his second paragraph, he says the punishment for treason is “if I’m not mistaken, death by firing squad.” He’s mistaken. US law doesn’t specify a method of execution for each crime, and most states use lethal injection. Only three people have been executed by firing squad since 1960, all of them in Utah. So you can add the US penal code to the growing list of topics this man knows nothing about but has opinions on anyways.

One more stylistic note: he has a “here’s my point” sentence, which is lazy writing on its own. Even worse, it’s in the last section of his article, only 3 paragraphs from the end. You shouldn’t have to tell your audience what your point is 80% of the way through your essay. If they haven’t figured it out on their own by then, you have bigger problems.

Perhaps the most poignant section of Weber’s piece is a vignette about a time he had dinner with an academic acquaintance. Weber turns the conversation to the scientific illiteracy of his colleagues, and the acquaintance makes a dismissive statement and changes the subject. Weber calls him on the fallacy, and rather than engage in debate, the acquaintance moves on and doesn’t call him again.

You can feel the discomfort of his poor dinner date in that passage. Here is someone who probably just wants to network, stuck in a restaurant with a man who won’t stop ranting about global warming and complaining about how stupid his colleagues are. He tries to change the subject, but the tenured professor won’t let him.

Earlier, Weber refers to the colleague who forgot how greenhouses work as “our department’s self-appointed expert on climate matters”. From what he’s said of how he talks to his students and coworkers, I am 99% certain that the only self-appointed expert in his department is him.

Finally, I want to talk about the stylistic choice that makes Myles Weber’s piece the peak of pretentiousness in academia: the way he spells “academia”.

Or rather, doesn’t: he uses “academe” instead, a word I’d never seen before. At first, I thought, “oh, he’s probably using the the pretentious original Latin term to be technically correct”. But I was mistaken. “Academia” isn’t just correct English, it’s correct Latin. So where did “academe” come from?

Well, it /is/ technically a word, but not a common one. It’s a synonym of “academia”, and doesn’t add any nuance or specificity beyond that. There’s no reason to use it, unless you want to show off how many big words you know.

It’s also synonymous with “Pedant”.

Halfway Around the World

As fun as it is to mock morons for believing stupid things, this article and its many flaws should be sobering to all of us. Mark Twain once said “A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on”, and never has that been more true than today’s massively online age. This misinformed piece has nearly 400 comments. It’s been read by thousands, even tens of thousands, of people. It came out, they read it, internalized all the nonsense it spewed, and moved on, all in just a few days.

And it took me two weeks to research and finish this response.

Today, two weeks is an eternity. Two weeks is longer than the lifespan of most memes. Reddit threads and Facebook posts disappear from your news feed in a matter of hours. By the time other thinkers can prepare their critiques, the misinformation has already come and gone. It’s old news, accepted into the general narrative, and attempts to correct it come across as necroing old threads that aren’t relevant anymore.

But they are relevant. Just because hard research moves at a comparatively glacial pace doesn’t mean it’s any less crucial today. Misinformation thrives on our impatience. It’s how, six years later, a tenured professor still believes that Barack Obama politicized Sandy Hook to push climate action, even though he never did. It’s how this article manages to change minds and move the conversation even though none of it is true. It’s how I got away with using that quote about lies traveling halfway around the world, even though Mark Twain didn’t actually say that.

In the end, Myles Weber and I agree. Healthy skepticism is a good thing, and something isn’t true just because a bunch of experts in white coats say it is. As long as the internet is free, there will be morons out there using it to peddle pseudoscientific dogma, and when fact-checkers can’t keep up, we have an obligation to watch out for them on our own.

As a rule of thumb, they’re usually the people urging you not to believe the experts.