Introduction

Ten years ago, a few magic players on a long-since defunct forum got together to answer a simple question: assuming you can’t go infinite, just how much damage can you deal in a game of Magic: the Gathering?

At first, they dealt damage in the hundreds, then the thousands, then the tens of thousands. Before long, they were dealing more damage than we have -illions to describe them. They even found decks which dealt so much damage that you needed powerful mathematical concepts to describe the numbers involved without breaking the universe. I’ll explain some of those concepts later, like Knuth up-arrow notation and Conway chains, but consider this a warning: the rest of this article will involve math, and a lot of it.

Unfortunately, these new decks are too complicated for anyone, even a skilled player, to understand how they work just by looking at a list. Instead, we post write-ups explaining how the damage is done, section by section. You may have seen this one before, which used the Vintage cardpool to deal 408 up-arrows worth of damage on turn 1 (we’ll get to what that means in a bit). It’s well-known on Reddit, and for three years, it was the gold standard for this challenge.

Until today.

The deck in this post deals more damage than the old vintage challenger. In fact, it deals so much damage that I can’t even tell you how many up-arrows it achieves: that number itself requires too many up-arrows to describe.

It deals more damage than Graham’s Number.

It is also Standard-legal.

Special thanks to Deedlit11 and lijil on the MtgSalvation forums for helping make this deck possible.

The Rules of the Game

I’ve taken the liberty of adapting the rules from the original vintage challenge to this one. I’ve relaxed them in some places to allow for the limited cardpool, but for the most part I’ve left them as-is.

- Start with a Standard-legal deck of exactly 60 cards. No less, of course, and if we allowed more, you could deal arbitrary but finite damage by including as many copies of Rat Colony as you feel like, and it wouldn’t break the other rules.

- Conditions caused by randomness can resolve any way you like. In this deck, that mostly means that every single card draw is a Demonic Tutor in disguise: you can assume that the order of your deck is exactly what you want it to be. This veers pretty heavily into magical christmasland, but if we didn’t do it this way you’d have to figure out the average amount of damage a deck could deal, which is probably impossible.

- The opponent is a goldfish with a deck of 60 random basic lands. However, they are still playing to stop you: if you give your opponent a choice, they will pick whichever one is worse for you. The only exception is that they won’t concede the game. This is a sadistic goldfish that wants to make you play it out.

- No going infinite. Infinite really means “arbitrary” in magic, most of the time, so we define it like this: when you make your deck, I pick a finite number, say, a million, or Graham’s Number, or four. If, no matter what number I pick, there’s a line your deck can take that will deal at least that much damage, your deck goes infinite and is disqualified.

- This doesn’t matter to our deck, but other rules of magic apply: if I put 80,000,000 copies of Shock on the stack and target my opponent with each one, they’ll die on the tenth one, and I’ll have dealt only 20 damage. In practice, that means you’re either winning with a giant X-spell or by attacking with a lot of very big creatures.

- In the old challenge, you had to go off on turn one. Here, that rule is relaxed, with a caveat: the fewer turns required, the better. No one is impressed that you can deal a lot of damage on turn 50, or 50 million for that matter. This deck, for instance, goes off on turn 6. You’ll need an awfully good reason to justify going later than that.

Important Terms to Know

Up-Arrow Notation

First off, let’s talk about up-arrow notation. It sounds (and looks) kinda scary, but the truth is that you’ve probably already used up-arrow notation before, when you were bored in math class and messing around with those unnecessary buttons on the side of your graphing calculator. If you’ve ever put in some small number and mashed the “10x” button, you were taking advantage of Knuth up-arrows.

Think about what you do when you add 10 to something, or multiply 10 by something, or raise 10 to some power. You know from elementary school that, in a way, each of these is the same as doing the last one over and over: 10*3 is the same as 10+(10+10). Add 10 to itself, with 3 10s. 103 is just 10*(10*10). Multiply 10 by itself, with 3 10s. That’s good enough for most numbers you’ll ever need to think about, like 30, or 1,000, or the chances you’ll win the lottery today and then get struck by lightning, or the number of atoms in the universe. But there are other numbers, like the amount of time until the inevitable heat death of the universe, or the number of different games of chess you could play, where it starts to get ugly: you have to write it like 1010120, and the exponents get smaller and higher until it’s unreadable. It would be really nice if you could have a function that works for exponents the way exponents work for multiplication. That’s what up-arrow notation is all about.

Let’s start with one up-arrow: A^B. That’s the same as exponents: A^B is the same as A*(A*(A*(A*(…(A*A))))), with B A’s in between. For instance, 2^3 is 8, 2^4 is 16, 2^5 is 32, and so on. Note the parentheses I added there, those will be important later.

Now, let’s add another arrow: A^^B. That’s the exact function we wanted earlier: A^^B is A^(A^(A^(…(A^A)))), with B A’s in between. For example, 2^^3 is (2^(2^2)), or 2^4, or 16. 2^^4 is 2^(2^(2^2), or 2^16, or 65,536. 2^^5 is 2^(2^(2^(2^2))), or 2^65,536, which has roughly 20,000 digits and is much larger than the number of atoms in the universe.

Remember that ugly 1010120 number I had earlier, the number of possible chess games? With up-arrows, we can estimate that as “somewhere between 10^^3 and 10^^4”.

You can keep going past that, adding as many arrows as you want. 2^^^3 is 2^^(2^^2). 2^^2 is 4 (in fact, no matter how many up-arrows you put between them, if both numbers are 2, the answer is 4: the same way 2+2, 2*2, and 22 all equal 4) , so 2^^^3 is the same as 2^^4, or 65,536. 2^^^4, however, is 2^^(2^^^3), or 2^^65,536. So, instead of having 20,000 digits, 2^^^4 is a chain of 2222…, getting higher and higher… with 65,536 2s. That’s already much, MUCH bigger than any of those numbers earlier.

That was with three arrows. The Vintage challenge had over four hundred of them. This list has… more.

Layers

Another important term is “layers”. A layer is essentially a combination of cards that uses up a small amount of one resource (say, copies of Priest of Titania) to make a very large amount of another resource (say, green mana). Those resources can be anything: tokens with an ability you can tap, mana, triggers on the stack, etc. What’s important is that you aren’t just converting between them, and that the amount of your output scales: you don’t just turn one Priest of Titania into one green mana, you turn it one Priest of Titania into A LOT of green mana, and the amount of green mana you make gets bigger each time you do it.

If you’re confused, here’s an example from the very first write-up anyone ever made for this challenge, way back in 2009:

Imagine you have four copies Kiki-Jiki, Mirror Breaker on the battlefield, along with a Mirror Gallery so they don’t die. You also have a Doubling Season, so any token-making effects you have get doubled, and an Opalescence, so all your enchantments, including Doubling Season, are creatures.

You tap the first Kiki-Jiki, targeting Doubling Season. That makes a token copy, but we have a Doubling Season out, so it actually makes two. Now, you have three Doubling Seasons.

You tap the second Kiki-Jiki, also on Doubling Season. This time, we have three of the enchantment, so the one token we make gets doubled to two, then doubled again to four, then doubled again to eight, so you wind up with 8+3=11 copies of Doubling Season.

You tap the third Kiki-Jiki the same way. Now, it gets doubled 11 times, making what I’ll just tell you is 2,048 Doubling Seasons. Combine that with the 11 you had earlier, for 2,059.

Then you tap the fourth Kiki-Jiki. It makes 22059 copies of Doubling Season. If you’re like me and you don’t know any powers of 2 past 2048, you’ll have to reach for a calculator for that one, but I’ll save you the wasted trip: your calculator can only handle numbers up to 100 digits. The number of Doubling Seasons you just made has 620.

66,185,

228,

434,

044,

942,

951,

864,

067,

458,

396,

061,

614,

989,

522,

267,

577,

311,

297,

802,

947,

435,

570,

493,

724,

401,

440,

549,

267,

868,

490,

798,

926,

773,

634,

494,

383,

968,

047,

143,

923,

956,

857,

140,

205,

406,

402,

740,

536,

087,

446,

083,

831,

052,

036,

848,

232,

439,

995,

904,

404,

992,

798,

007,

514,

718,

326,

043,

410,

570,

379,

830,

870,

463,

780,

085,

260,

619,

444,

417,

205,

199,

197,

123,

751,

210,

704,

970,

352,

727,

833,

755,

425,

876,

102,

776,

028,

267,

313,

405,

809,

429,

548,

880,

554,

782,

040,

765,

277,

562,

828,

362,

884,

238,

325,

465,

448,

520,

348,

307,

574,

943,

345,

990,

309,

941,

642,

666,

926,

723,

379,

729,

598,

185,

834,

735,

054,

732,

500,

415,

409,

883,

868,

361,

423,

159,

913,

770,

812,

218,

772,

711,

901,

772,

249,

553,

153,

402,

287,

759,

789,

517,

121,

744,

336,

755,

350,

465,

901,

655,

205,

184,

917,

370,

974,

202,

405,

586,

941,

211,

065,

395,

540,

765,

567,

663,

193,

297,

173,

367,

254,

230,

313,

612,

244,

182,

941,

999,

500,

402,

388,

195,

450,

053,

080,

385,

548.

That is one layer: it turns untapped copies of Kiki-Jiki, Mirror Breaker into an exponentially greater number of Doubling Seasons.

We can add more layers on top of that. Let’s say we had Serra’s Sanctum and Djinn Illuminatus out, too. Then, we could tap the sanctum for 2^2059 mana (not gonna write it out again), and spend it all to replicate a Burst of Energy on Kiki Jiki, untapping it each time…

That would get you to about 2^^^4 Doubling Seasons. You might remember that number from earlier as our giant tower of 2s.

Note that, even though adding extra Doubling Seasons to start would vastly improve the damage total, adding extra Kiki-Jikis instead got us a lot more bang for our buck, and adding a Burst of Energy got us even more. The same thing applies to Burst of Energy: we could add a second Burst, or we could add a Gaea’s Cradle to get us all the green mana we need, and play Fossil Find 2^^^4 times. Each copy could get back Burst of Energy again, which would let us play and replicate it even more…

That’s how the old challengers worked: they would put a lot of layers into their deck, where the output resource of one was the input resource of another. One Fossil Find turns into lots of Burst of Energy, each of which turns into lots of untapped Kiki Jikis, each of which turns into lots of Doubling Seasons. If you line them up properly, 1 layer = 1 arrow in your final damage count. It also helps you avoid infinites: as long as you make sure that each new layer uses up a new resource, one you can’t already generate lower down, you can’t set up an infinite loop.

After that, it’s just a matter of how many different resources you can cram into the 60 card limit.

How did they fit 408 layers into that few slots? The short answer is, they doubled up. They made it so that the deck could, rather than just creating lots of Doubling Season tokens, also create copies of cards which would duplicate the other layers. These could be the usual suspects, like Minion Reflector, Swarm Intelligence, and Panharmonicon, or cards you wouldn’t expect like Clash of Realities. I won’t go into too much detail, but I encourage you to read their article if you’re curious.

The key is that, by using these “engine cards” to add extra layers of triggers to several different parts of the combo, they could make it so that one card could add as many as FIFTEEN layers to the final damage total!

Once you get up to the hundreds of arrows, writing them all out in a row gets real unwieldy. Instead, we use something called Conway arrow chains. We’ll get into the more complex cases later, but the simple version of a Conway arrow chain is that a->b->c is the same as a^^^…^^^b, with c arrows in between. 2^^^4 is also 2->4->3. Note that the order of the numbers changed, so the arrows are on the right: the reason is that in Conway chains, the further to the right a number is, the bigger an impact it has. We know that adding an arrow makes a bigger number than adding one to the right-hand number, so the arrow count comes afterward.

This is important, because that way I can tell you that the Vintage deck dealt 2->20->408 damage, instead of 2^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^20.

Graham’s Number

Now that we’ve covered up-arrows and layers, what is Graham’s Number? Graham’s Number is, or was for a long time, the largest number ever cited in a mathematical journal. If you want to know what it actually represents, there’s a great Numberphile video about it here. For our purposes, we only care about the value: it’s our target.

To get to Graham’s number, you start with a very large number: 3^^^^3. That is already so vast that, if you were to somehow visualize the entire value, every digit, in your head, your brain would spontaneously collapse into a black hole which would instantly absorb all matter in the universe. Sort of. Its event horizon would be wider around than the observable universe, but I’m not sure whether everything would immediately reach the singularity, so it really depends on your definition of “absorb”… I’m getting sidetracked.

Anyways, take that number, 3^^^^3. Call it G(1). G(2) is then 3^^^…^^^3, with 3^^^^3 ARROWS in between the 3s. Before we go any further, take a moment to think about what that means. We’ve gone from one arrow, to two, to three, and already we’ve reached the point where it’s hard to visualize what’s happening in our head. Then we made the jump to 408 with the Vintage combo. And now, I’m asking you to imagine more than a googolplex up-arrows. That’s what it takes to get to G(2).

G(3) is 3^^^…^^^3, with G(2) arrows. G(4) is 3^^^…^^^3, with G(3) arrows, and so on.

Graham’s Number, the number this deck outmatches, is G(64).

Can I Get a Decklist?

You can see the full list for the deck below. Feel free to give it a whirl, though you’ll probably be disappointed with the results. 13 lands, five colors, more 4+ drops than lands, five colors, almost all singletons, it’s a mess. Outside of the exact scenario of this challenge, it will struggle to ever get anything done at all.

And yet… If everything goes right, on turn 6, it will deal more than Graham’s Number damage in a single turn, with no infinite combos.

In Standard.

Botanical Sanctum

3x Llanowar Elves

Blooming Marsh

Rashmi, Eternities Crafter

Spire of Industry

4x Aether Hub

Unclaimed Territory

Gideon, Martial Paragon

Oath of Teferi

2x Island

4x Anointed Procession

2x Sparring Mummy

Merfolk Branchwalker

Planar Bridge

Patient Rebuilding

Ghirapur Orrery

Panharmonicon

Cogwork Assembler

Raff Capashen, Ship’s Mage

Samut, Voice of Dissent

Sea Legs

Nissa, Genesis Mage

Raging Swordtooth

Seal Away

Djeru’s Renunciation

Slinn Voda, the Rising Deep

Naru Meha, Master Wizard

Naru Meha, Master Wizard

Demystify

Deeproot Champion

Switcheroo

Unwind

Onward//Victory

Marwyn, the Nurturer

Baffling End

Thorn Lieutenant

Teshar, Ancestor’s Apostle

Paladin of Atonement

Muldrotha, the Gravetide

Key to the City

Dynavolt Tower

Bloodwater Entity

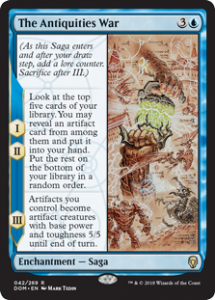

The Antiquities War

4x Silent Gravestone

Forsake the Worldly

Section 0: Setup

Turn 1 starts out pretty inocuously: Botanical Sanctum, Llanowar Elves, go. So far, we’re still in the realm of sanity.

Turn 2 is similarly dull: We play Aether Hub, getting an energy, and tap out to play our Marwyn, the Nurturer.

On turn 3, we start to see the foundations of the spice in the combo: we open up with Blooming Marsh, and tap everything but Marwyn to play Rashmi, Eternities Crafter. Rashmi is an elf, so Marwyn triggers and gets a +1/+1 counter. She now taps for GG, not just G. We do so, and use one of the mana produced to play a second Llanowar Elves, getting another +1/+1 counter.

After a while, the setups for these combos tend to take a certain shape. Turns 1-3 tends to be a sequence of playing as many mana elves and rocks as possible. Turn 4 uses all that mana to dump a hand full of draw engines and planeswalkers, which in turn let us get enough mana and cards for turn 5, which draws the entire deck and dumps everything onto the battlefield, at the cost of all the available resources. Then, we untap and go off on turn 6. The same pattern plays out here.

Turn 4: tap out (besides one elf) to play Nissa, Genesis Mage. Rashmi triggers, and we reveal and cast Panharmonicon. +2 Nissa, untapping Marwyn, the tapped elves, Botanical Sanctum, and an Aether Hub. Tap an Elves to play a third Llanowar Elves, making Marwyn trigger twice and become a 5/5. Tap Marwyn and our Botanical Sanctum to play The Antiquities War, which reveals Ghirapur Orrery. We still have 2 mana floating, as well as an untapped Llanowar Elves and an Aether Hub. Spend those to play Orrery, and pass the turn, hellbent.

Turn 5: last setup turn, I promise.

First, we draw 3 cards with Ghirapur Orrery in our upkeep. Then we draw our card for the turn. Then The Antiquities War triggers, and we reveal Cogwork Assembler and put it into our hand. We have 5 cards available now, which will be enough to give us access to everything else we need in the deck.

We start by playing Spire of Industry, tapping Marwyn for 5 and the spire for W (down to 19 life), and spending all but 1 of that mana to play our second underpowered Planeswalker-deck centerpiece, Gideon, Martial Paragon. Rashmi triggers, and we reveal and cast Anointed Procession. We tap our three Llanowar Elves, giving us 4 green mana in the pool, and +2 Gideon, untapping all our creatures and giving Marwyn +1/+1 for the turn, making her tap for 6. We tap them all again for 9 mana, play Cogwork Assembler, and use the remaining 6 mana to play Planar Bridge.

Then we +2 our Nissa, Genesis Mage, untapping Marwyn, a Llanowar Elves, Spire of Industry, and Botanical Sanctum, making sure to tap the Sanctum for U before anything else. We tap everything we have, for a total of 11 mana. Oh, and make sure one of that mana is red from Spire of Industry, bringing us down to 18 life.

Then we spend 8 of that mana and activate Planar Bridge, searching out Oath of Teferi. We have it trigger Ghirapur Orrery, so only Ghirapur Orrery (which is useless for the rest of this turn) gets exiled. We can now activate both our Planeswalkers again, so we do: Gideon’s +2 untaps all three Llanowar Elves and Marwyn while pumping Marwyn up to 7/7. We tap them to add 10 more mana to the 3 we had left after activating the Bridge, giving us 13 total mana. Nissa untaps Marwyn, an Elf, and two lands, giving us another 10 mana, up to 23.

We spend the first 7 of that to activate our Cogwork Assembler, targeting Panharmonicon. This is something we’ll do a lot later on: by turning enters-the-battlefield triggers into mana, and that mana into Panharmonicons, we can turn each enters-the-battlefield trigger on our creatures into a layer resource. It’s the core engine of our deck.

In this case, we create two copies of Panharmonicon, since we have one Anointed Procession. Between them, the original, and the native trigger, we’ll get 4 triggers from any creature entering the battlefield.

The next 7 we spend copies Planar Bridge, making two tokens. The legend rule kicks in, and we immediately sacrifice the nontoken and one of the tokens, leaving us with an untapped Planar Bridge. We still have 9 mana in the pool, so we spend all but the one red we generated to tutor another permanent directly onto the battlefield: Sparring Mummy. It triggers four times, and we have all of them target Marwyn.

Each trigger lets us tap Marwyn for another 7 mana, so when they’ve all resolved, we’ll wind up with 29 total mana, counting the one red we’ve saved. That’s enough to activate Cogwork Assembler again to make two more Panharmonicons, spend another 15 to copy Planar Bridge and tap the copy to search for a second Sparring Mummy, and still have 6 G and an R in our pool. The second one triggers six times now, which will give us 42 mana, 48 if you count what we have floating.

Almost. We can do slightly better than that. If we spend 21 mana we get from the first three triggers on copying Panharmonicon immediately, before letting anything else resolve, we can get up to 11 total Panharmonicons, causing future creatures to trigger ETB abilities 12 times. Then, we can let the next two triggers resolve, giving us a total of 19 green mana and one red, with one untap trigger still on the stack.

At that point, we can spend the one red we’ve been saving and 2 of that green mana to play the last card from our hand: Onward//Victory, targeting Marwyn. If we let it resolve now, Marwyn would tap for 14 on the next trigger, but that’s not good enough for us.

Instead, we spend another 15 of our mana, leaving us with only GG in the pool, to create and activate another Planar Bridge copy. This time, we search for Naru Meha, Master Wizard. Her ability triggers 12 times, and each time copies Onward//Victory, targeting Marwyn.

The first one gives Marwyn +7/+0, giving her 14 power. The second gives her +14/+0, giving her 28. The third brings her up to 56, the fourth to 112, and so on, until the twelfth trigger resolves, leaving Marwyn a 28,672/7 creature.

Then the original Onward//Victory resolves, her power gets doubled again, leaving her a 57,344/7 creature.

We could end the game right now. After the last Mummy trigger untaps Marwyn, we could swing with her, bring our opponent down to -57,324 life, and go home. We won’t. We have greater things in mind.

Section 0.5: “Drawing” our Deck

Instead, we tap Marwyn for 57,344 green mana. Combined with Cogwork Assembler/Planar Bridge, that’s almost enough to tutor out every permanent in one commander deck… for every single color combination possible. Needless to say, it’s enough to search out all the permanents we need from our deck. In our case, that’s three more Aether Hubs, an Unclaimed Territory which we set to Human (we MUST set it to human, or this entire combo becomes impossible), two Islands, Raff Capashen, Ship’s Mage, Deeproot Champion, Baffling End (which has no targets), Muldrotha, the Gravetide, our remaining three Anointed Processions, Key to the City, Samut, Voice of Dissent, Dynavolt Tower, and Patient Rebuilding. That subtracts a total of 255 mana from our 57,346 (remember, we also had GG floating beforehand). We can spend another 22 to make 16 more copies of Panharmonicon and tutor out our Merfolk Branchwalker, which will explore 22 times. We use that to mill Paladin of Atonement, Teshar, Ancestor’s Apostle, Slinn Voda, the Rising Deep, a second Naru Meha, Master Wizard, and Sea Legs, as well as get a lot of +1/+1 counters. Then we spend another 15 to search out Bloodwater Entity, putting Onward//Victory on top of our library. From that point, we have almost all the pieces in place to start the combo, and 57,054 green mana left in our mana pool. We just need something to do with it.

We can start by spending 57,036 of that to activate Cogwork Assembler 8,148 times, targeting Panharmonicon each time. That creates a total of 130368 copies, which, combined with the 16 we made in the last paragraph and the 5 we made earlier, gives us 130,389 Panharmonicons. Each enters the battlefield trigger will happen 130,390 times. We still have 18 mana floating, enough to make a Planar Bridge copy and use it to search out Thorn Lieutenant.

Marwyn triggers 130,390 times, getting 130,390 +1/+1 counters. Unlike the boost we gave her with Onward//Victory, these will stick around, so we’ll start next turn with a 130,395/130,395 legend.

Now, at long last, we pass the turn. We are still hellbent, and have only 13 cards left in our library: Seal Away, Djeru’s Renunciation, Demystify, Unwind, Onward//Victory, Forsake the Worldly, Switcheroo, Raging Swordtooth, three Silent Gravestones, and, of course, two Yargle, Glutton of Urborg. We’re at 18 life, and have 4 energy from our 4 Aether Hubs. All our creatures have haste, thanks to Samut, and all our historic spells have flash, thanks to Raff Capashen. All the token copies of our artifacts disappear, including our only Planar Bridge.

We are ready to begin.

Section 1: Starting up the Megacombo

Come turn six, both Patient Rebuilding and Ghirapur Orrery trigger. Put the Orrery trigger on top. We’re hellbent, so we draw three cards. Then, Patient Rebuilding triggers. Our opponent’s deck is all lands, so it draws us another three. In our draw step, we draw another, seventh card, so when we enter our main phase, we have a full grip of 7. At that point, The Antiquities War triggers, and its third chapter ability goes on the stack. Don’t let it resolve.

Our seven cards, by the way, should be all our instants (not Switcheroo), a Silent Gravestone, and Seal Away.

We start by casting Planar Bridge from our graveyard with Muldrotha, the Gravetide. That triggers Rashmi, revealing Switcheroo. We cast it, Dynavolt Tower triggers, and we go up to 6 energy (note: even though our opponent has no creatures at this point, we can still play it by targeting two of our own). The next few thousand words of combo will all take place with that spell still on the stack.

Immediately, we tap Marwyn for 130,395 green mana. We spend 7 of that to create 16 Panharmonicons (we need a reasonable amount of those to get us started), hold 27 in reserve, and spend the remaining 130,361 to create as many copies of Dynavolt Tower as we can: 297,968, to be precise.

Now that that’s done, we cast our instants (except Forsake the Worldly) from our hand, waiting until all the Dynavolt Tower triggers resolve each time so the stack looks like:

Djeru’s Renunciation

Demystify

Onward//Victory

Unwind (targeting Switcheroo)

Switcheroo

Planar Bridge

The Antiquities War, Chapter III

That costs us 1 life and 2 energy for the Renunciation, Demystify, and Onward//Victory, since we have no lands that innately tap for red or white, so we go down to 17 and 4 energy. Of course, we also generated 595,936 energy for each instant and sorcery we cast, so we actually have 2,383,748 of it, not 4. It also forces us to tap one of our Islands for Unwind, and spend 5 of our remaining green to pay for the generic costs. We can make up for that, though, by tapping our three Llanowar Elves for GGG, leaving us with 25 mana floating. From there, we spend 20 energy and activate four of our Dynavolt Towers to deal 12 damage to our own Nissa, killing her. Not for long, though, because after that we’ll cast her again with Muldrotha, leaving her on the stack. We also tap a second Island to play Sea Legs, leaving it, too, on the stack. We have 18 mana left.

Then, we cast Slinn Voda from our graveyard, kicked. That leaves us with 11 mana floating, and taps both of our fastlands and a third Aether Hub (only 2,383,727 energy left!). It enters the battlefield, and its ability triggers 18 times.

We let the first one resolve, bouncing all of our creatures back to hand. Immediately, we spend 2 more mana and tap Unclaimed Territory and our final Aether Hub to play Naru Meha, Master Wizard. Her ability triggers 18 times, and we target Unwind with the top 3 and Onward//Victory with the rest.

The first Unwind copy targets Planar Bridge, which gets countered and lets us untap Unclaimed Territory and two of our Fastlands. We tap those for a W we can only use on humans, a U, and a B, then let the second trigger resolve. The next one Unwinds Nissa, untapping the same lands again. This time, we tap them for a humans-only R, and UU. The third one counters Sea Legs, and we untap our fastlands and an island, tapping them all for U. All told we have 9 G, 6 U, 1 B, and an R and W that we can only spend on humans.

Before any Onward//Victory triggers resolve, we cast Raff Capashen with a U and our W (7 green floating), and follow it by replaying Marwyn and Samut, Voice of Dissent. That leaves us with no green, but an untapped hasty Marwyn.

And 15 copies of Onward//Victory on the stack.

Each one can target Marwyn, pumping her until she becomes a 32,768/1 creature. We tap her for 32,768 mana, and spend 32,739 of that (how much we hold in reserve no longer matters, it’s just noise to us now) to create 74,832 more Panharmonicons. The next enters-the-battlefield ability we get will trigger 74,850 times.

The next Slinn Voda trigger to resolve lets us do that whole process again. We have 29 G, 5 U, and 1 B on the stack, which is enough to cast Muldrotha, Nissa, Planar Bridge, and Sea Legs, then play a Naru Meha and use the top 3 triggers to Unwind our 3 noncreatures to generate 9 land untaps, with 1 U still floating. After we cast Raff Capashen and Samut, resolve our 74,847 copies of Onward//Victory, and tap Marwyn for an amount of green mana with over 20,000 digits, we’ll be able to end with 29 G, 1 B, and 5 U, and one mana of any type a land we have can produce, as well as a 20,000-digit number of Panharmonicons. In other words, every time we resolve a Slinn Voda trigger, we get one more untap of our lands than we need, letting us stockpile colors of mana other than green. We can, of course, effectively ignore any generic or green mana costs from here on in, because Marwyn is already generating so much.

We won’t use all the Slinn Voda triggers that way. They’re much too valuable. But we will use a couple: nine, to be precise. We also won’t be playing Marwyn every time: after we generate the first 20,000-digit amount of green mana from the second Slinn Voda trigger to resolve, we’ll spend most of that to make an uncountable amount of Panharmonicons, hold enough green mana in reserve to pay for the future costs for the next few triggers to resolve (a googol should be enough), and skip playing Marwyn later on. That means we no longer have to spend a land untap on red mana for Samut each time, so every time we resolve another Slinn Voda trigger, we’ll untap 9 lands, and have to spend only 7 mana requiring us to tap a land again (2 for Raff Capashen, 2 for the UB in Muldrotha’s cost, 2 for Naru Meha, 1 for Sea Legs), so we profit 2 for every one Slinn Voda trigger. That’s good, because we’ll need 18 spare mana to go off, and we want to save our triggers here.

Section 2: Building the stack

On the last of those triggers, we’ll do things slightly differently. First, we won’t counter Planar Bridge with Unwind, we let it resolve, casting the Silent Gravestone from our hand and countering it instead. Second, before we play Naru Meha, we’ll spend an energy and one of our untaps to play Teshar, Ancestor’s Apostle from our graveyard, as well as make a copy of Key to the City and tap the copy to discard Thorn Lieutenant, which got bounced by Slinn Voda a while back. That way, when we cast Naru Meha, we can bring the Lieutenant back to the battlefield with Teshar’s trigger. Finally, we’ll use a few more of Naru Meha’s triggers to copy our other instants: first Demystify, destroying our Baffling End and giving our opponent a 3/3 dinosaur token, then Switcheroo, exchanging that token for our Thorn Lieutenant, then a few Onward//Victory on that Lieutenant, forcing our opponent to create several more 1/1 elves, and finally two more Switcheroos, swapping some of our opponent’s creatures for our Deeproot Champion and our Merfolk Branchwalker from last turn (remember, they don’t get bounced by Slinn Voda, which doesn’t affect merfolk).

Then, we let one more Slinn Voda trigger resolve, bouncing nearly every creature, but not our opponent’s merfolk, to our hand.

At this point, we can finally activate Planar Bridge, tutoring Raging Swordtooth directly into play. Its ability triggers many, many times, putting an uncountable number of “1 damage to everything” triggers on the stack. Before any of those resolve, however, we play Naru Meha from our hand again. This one will swap Raging Swordtooth for one of the merfolk we gave our opponent, then copy Djeru’s Renunciation, tapping the Swordtooth. Now, we spend another energy/life to play Seal Away from our hand, exiling our Swordtooth.

The first 8 Swordtooth triggers will kill both Naru Meha and Slinn Voda, but not the merfolk we’ve been swapping around (Branchwalker has several thousand toughness from all the exploring it did last turn, while Deeproot Champion has grown by +3/+3 for each Slinn Voda trigger, plus another 4 from casting our instants and Switcheroo). After that, we can play Raff Capashen, Muldrotha, the Gravetide, and finally Slinn Voda. That gives us an uncountable number of bounce triggers. We let the first one resolve, replay Raff Capashen and Muldrotha, and now that Muldrotha has been reset we can play our three Unwind targets, Naru Meha from the graveyard, and continue our combo like before.

That operation costs 18 land taps, by the way, so we have to let 9 Slinn Voda triggers resolve, plus 1 to bounce everything after we generate our mana, plus 2 to generate our starting pool of green mana. We had 18 to work with, so we wind up with 6 triggers left on the stack. On top of those are an uncountable number of Raging Swordtooth triggers, and on top of those are an equal amount of Slinn Voda triggers.

We don’t stop there, either. Every time we resolve a Slinn Voda, we’ll:

- Spend just enough of its triggers to generate all the mana we need for the remaining steps.

- Spend a life/energy to reanimate the Thorn Lieutenant.

- Use Naru Meha and Switcheroo to give our opponent both our merfolk.

- Use a Naru Meha trigger to copy Demystify, killing our Seal Away, and get back Raging Swordtooth.

- Play Naru Meha and use it to swap the Swordtooth for a Merfolk with Switcheroo and tap it with Djeru’s Renunciation, and spend a white mana and a life to exile it under Seal Away (remember, Muldrotha lets us replay it, and we keep bouncing and replaying Muldrotha right now).

Basically, we’re using some elaborate stack tricks to bounce Raging Swordtooth between the battlefield, our opponent’s side of the board, and exile, without ever letting it go to our graveyard or hand, where we’d have to cast it. In other words, we’re giving it flash, even though it isn’t historic. Critically, however, we can’t do this infinitely: even though we can copy our various instants and sorceries with Naru Meha essentially for free, Seal Away will still cost a white mana, and we can only produce that by spending either a life or an energy.

None of these elaborate tricks, by the way, would be necessary if Wizards had just reprinted Vedalken Orrery in Kaladesh. It would open up our options for more layers later, free up deck space, and make the whole deck much easier to follow, but they couldn’t be bothered to do us a solid.

I’m not mad.

Anyway, this is also why we have two copies of Naru Meha in our deck: because we need to spend some of its triggers to kill Seal Away and get back Swordtooh, and also need to spend some of its triggers to exile Swordtooth while the dinosaur’s triggers are still on the stack, we need to play its twice without bouncing him. Fortunately, with Muldrotha getting reset constantly, we can always cast them from the graveyard and bounce them.

The only other problem is getting back our Merfolk and Thorn Lieutenant. That’s what Teshar is for: it essentially gives them haste. The Merfolk don’t get bounced by Slinn Voda, so they let us keep at least a couple creatures on our opponent’s board at all times, and Thorn Lieutenant lets us give our opponent more if they get close to running out.

We keep doing this until we run out of energy and life to pay. We spend 2 of those resources every time we play Swordtooth, and we get a batch of Swordtooth triggers and a batch of Slinn Voda triggers each time, so when all is said and done, we’ll have a giant stack of alternating batches of Slinn Voda and Raging Swordtooth triggers, each one uncountably large. There will be one of these batches for every energy/life we had to spend. We had 2,383,727 energy and 17 life, so all told, we’ll have 2,383,743 batches of triggers on the stack. Technically, we’ll only have 2,383,742, because we can only spend life/energy in batches of 2, but we can count the topmost batch of Naru Meha triggers to balance it out.

If you thought this combo was hard to follow so far, this next part might melt your brain. I don’t want that to happen, so instead of jumping right in, we need to take a break to talk about the algorithm behind this deck.

How to Make Lots Of Arrows: A Primer on Two-State Machines

Set aside for a moment all the actual cards in these decks, and imagine them not as magic brews but as very simple programs. After all, that’s basically what they are: the different resources we have (blue mana, white mana, energy, life, triggers on the stack, etc.) are the memory, and the various ways we convert those resources into other resources are the instructions.

Remember how we talked about layers, where each one takes in some small amount of one resource, and turns it into an ever-greater amount of another resource? Think of each layer as an instruction: “use up one resource I to generate a lot of resource O”. There is one instruction for each layer, and by chaining them together with their different resources, we build our megacombo.

The problem with this approach is that it’s bounded: There are only so many different resources you can model with 60 distinct magic cards, and there is a constant number of arrows a single card can be worth. In the Vintage deck, that number was about 15, meaning that ignoring everything else, the most you could ever get without adding to that number somehow would be 900, nowhere CLOSE to Graham’s number.

The combo we’re about to implement works by fiddling with what instructions you can have your program execute.

First, we need to divide the resources we’ve used so far into two groups: true resources, and triggers. They can both be used for a layer, but there’s a critical difference: triggers, like from Minion Reflector, go on the stack, and all the rules of the stack apply: you can only spend them one at a time, and only when that specific trigger is on top of the stack. A resource, like green mana, is something you can use whenever you want.

Next, let’s actually imagine the instructions you’d use for three layers, a resource layer and two trigger layers. That would look something like:

- Spend one of resource I to put X copies of trigger A on the stack.

- Use up one trigger A from the top of the stack to put X copies of trigger B on top of the stack.

- Use one copy of trigger B to generate X O.

If we use our resource I one at a time, we’ll wind up with a stack that looks like this:

Trigger B

…

Trigger B

Trigger A

…

Trigger A

When you look at that stack, you can see another critical property of trigger layers, especially ones that come next to each other in your chain: once you’ve started an iteration of the trigger B layer, you’re committed: you can’t go back to the trigger A layer until all the trigger B is gone.

How much would that set above give us? We have 3 layers, so those would give us 3 arrows. For instance if we had 4 I, we’d end up with 2->4->3 O, the same as that giant tower of 2s we calculated earlier.

The biggest difference between the new combo and the three options I’ve described above is the introduction of the “state”. The state is a technical term in computation theory, but basically it’s a variable that determines what instructions your program can actually do. In your computer, the state could include, say, whether or not Microsoft Word is running: you can’t exactly do a spell-check without starting the application. In Magic, it might be whether or not you’ve activated a certain planeswalker this turn: if one of your instructions is “activate Nissa, Genesis Mage to untap a land, and tap it for lots of mana”, you can’t do that instruction if you’ve already activated her.

Note that not only can you only do certain instructions in certain states, performing an instruction can also change what state you’re in. In the Nissa example, once you do that instruction, you move to an “activated” state, and you can only do that instruction again if you find a way to move back, say, by bouncing Nissa.

In this new version, there are five moves:

- Spend one of resource I to put X copies of trigger A on the stack.

- If, and only if, the state is unlocked, use one copy of trigger A from the top of the stack to put X copies of trigger B on top of the stack, and lock the state.

- Use one copy of trigger B from the top of the stack to generate X O.

- Use one copy of trigger B from the top of the stack to unlock the state.

We’ll get to 5 in a minute.

So far, it’s similar to before. Let’s say you have five of resource I. You’d spend one to get lots of copies of trigger A. Then, you’d use one of those to create lots of copies of trigger B, and lock the state. You’d use most of those copies of trigger B to create more O, but when you got to the last one, you’d use it to unlock the state, which would let you use up the next copy of trigger A, and do the same thing over again. It’s slightly less efficient than the three-instruction, one-state game, but only by a little: we give up one one trigger B from each batch, which becomes insignificant as the size of our batches grows.

5. If, and only if, the state is unlocked, use one copy of trigger A from the top of the stack to generate one of resource I, and lock the state.

How does that fifth instruction change what we can do? Well, obviously we can do the same thing as we did with 4 instructions, and spend our I one at a time. We’ll wind up with a stack that looks like this:

Trigger B

…

Trigger B

Trigger A

…

Trigger A

When we’re down to our last B, we spend that to unlock the state. Then, we spend our second A to generate an I. Sweet! But now, the state is locked. We can spend that I and get lots of triggers of A, but we don’t care about copies of A on the stack: we care about how much O we can generate, and we can’t generate any O without making those A triggers into Bs. And we can’t make any of trigger B, because the state is locked! And, since we can’t unlock the state without a trigger B, we will never be able to use the rest of our trigger A on the stack. We fizzle out. No good.

What if we used all five of our I at once? Then, we have the exact same problem, just with way more copies of trigger A on the bottom of the stack:

Trigger B

…

Trigger B

Trigger A

…

…

…

Trigger A

It’ll still fizzle. It’s starting to seem like that fifth move is completely useless.

There is, however, one more option.

We start by spending an I to create lots of trigger A, as usual. Also as usual, we use one of trigger A to create a lot of trigger B, and lock the state. This time, however, we don’t start using trigger B to generate O immediately. Instead, we spend the first trigger B to unlock the state again, and spend another I to make ANOTHER stack of trigger A, on top of our first two! Then, we use one trigger A to make more trigger B, and we repeat until we’re all out of I.

The end result will be a stack that looks something like this:

Trigger B

…

Trigger B

Trigger A

…

Trigger A

Trigger B

…

Trigger B

Trigger A

…

Trigger A

Basically, we’ll have these batches of trigger B and trigger A, one on top of another. With five of resource I, we’ll have five batches each, or ten total.

The first two batches proceed the same way we did with four instructions. We only when we get to the very last copy of trigger A in the second batch. Then, and only then, we use move 5, spend our last A to generate one more I, and lock the state.

We know what happens now. We need a trigger B to unlock the state, and we can’t make any more of trigger B now that the state is locked, so we fizzle. Right?

Wrong! This time, we have a trigger B: right below us, in the next batch down. We use one of those to unlock the state, and now we’re free to use our new resource I to make a new, much larger batch of trigger A. Now, the stack looks exactly the same as it did before, with two differences:

- Because we’ve made a lot more O, the top two batches of trigger A and trigger B on the stack are way bigger now than they were when we started.

- We have one fewer trigger B in the third batch from the top.

Do you see what’s happening? Instead of using each trigger B in the lower group to make lots of our output resource, we can use each one to make a new, much larger batch of trigger A. And when we’re almost out of that new batch, we can do the same thing again: use its last trigger, plus a trigger B below it, to run through the trigger A layer a third time. We can keep doing that until we run out of trigger B, then use a trigger A below THAT to make a new, much bigger batch. We’re feeding the same two layers into each other.

Why doesn’t this go infinite? It comes down to timing. In order to make one resource I, you need a both a trigger A to feed into step 5, and a trigger B to unlock the state with step 4. But because you need to unlock the state after generating your resource I, the trigger B has to be under the trigger A on the stack. That means they can’t come from the same source: remember, the rules of the stack make it so that once you convert one trigger A into a batch of trigger B, the B’s go on top and you can’t access that batch of A again until they’re gone.

The problem there is, that trigger B lower down on the stack has to come from somewhere. For it to be there, you have to have another batch of trigger A somewhere below it. But since you can’t add stuff in between triggers in a single batch, that means you must have spent an additional I to generate that other, lower batch.

In other words, to have the opportunity to get back one I, you must have already spent two I earlier on.

Once you’ve generated your I, you have two ways to get more. You can resolve past any remaining trigger B on the stack until you get to the next batch down of trigger A, use up the last one of those to make your second I, and use a trigger B below THAT batch to unlock the state. But then, you hit the same problem: where did that trigger B come from?

You could also spend your new I to make a new batch of trigger A, go through it like usual, and use the last one of it to make a new I and the next trigger B down to unlock the state. But then, you’re spending the resource you just got in order to generate a replacement. You can never build back up to two I that way.

It is mathematically impossible to run these instructions in a way that won’t eventually run out of I to use. We are still finitely bounded.

What does all this get us? Well, the top two layers of triggers work like the old version. But the next batch of trigger B can each regenerate the entire top two batches, so the second batch down represents a third layer. Then, the batch of trigger A below that represents a fourth. The trigger B below that trigger A can regenerate all three batches above it, and so on.

In the old version, with 4 I, we made 2->4->3 O. In this version, we make 2->3->8 O. If we added a fifth I, we’d have 2->3->10.

In this combo, each new resource I we get doesn’t add 1 to the number on the right side of our arrows. It adds TWO ARROWS.

Oh, and if that structure of alternating triggers seems familiar to you, that’s because we just spend an entire section building it out of Raging Swordtooth and Slinn Voda triggers. All in good time.

I know that all seems complicated, but you don’t have to understand everything about two-state machines to make sense of this. All you need to understand is that if we can implement those five instructions with magic cards, without allowing any corner cases, we can turn one resource I (say, white mana) into one arrow. This operation is called an “Ackermann stage”, or just a “stage” for short. For the record, I voted for calling it “The Omega Combo”, because it also implements the omega (ω) ordinal in the Fast-Growing Hierarchy, but you win some, you lose some.

It takes 17 cards for us to do it. It’s a convoluted mess of a combo that would be impossible to explain in one gulp. Instead, we’re going to walk through the combo instruction-by-instruction, breaking it down into five manageable pieces.

Section 3: The Megacombo

Now that we understand what the end goal of this combo is, let’s put the pieces together and see how we implement it.

The output resource: Green mana/Panharmonicons

![]()

You’ve already seen this at work. Once we get to the very top layer, we’ll replay Marwyn and our legends, play Naru Meha and point a bajilion Onward//Victory copies at Marwyn, and tap Marwyn for 2^X mana, where X is the number of Panharmonicons we’ve created. We spend all that to make even more Panharmonicons, and the next time we play Naru Meha, we’ll get much, much more mana for our trouble. That requires bouncing Naru Meha, which brings us to…

Trigger B: Slinn Voda, the Rising Deep

Like when we were setting up, we can leverage each Slinn Voda trigger to bounce both Marwyn and Naru Meha, giving us another iteration of that output-generating layer. That’s not enough for our stage-combo, though: we also need that to lock the state. That’s where Muldrotha comes in. We have no way to bounce Slinn Voda, but we can kill her and replay her with Muldrotha. Once we do that, we can’t replay her anymore, until Muldrotha gets bounced and replayed. That resets our Elemental Avatar, at the cost of one Slinn Voda trigger. In other words, we can use one trigger B to unlock the state. We just need a way to kill Slinn Voda…

Trigger A: Raging Swordtooth

This one works the same way it did when we were building the stack: we resolve Raging Swordtooth triggers 8 at a time to kill Slinn Voda, which lets us replay the leviathan with Muldrotha and get another iteration of the upper layer. This, in turn, costs us one input resource: either life or energy. Earlier, it cost us 2, because we had to play both Seal Away and Teshar, Ancestor’s Apostle, but later on, we’ll be casting Teshar right before the Swordtooth anyway, so that won’t change the math.

I won’t go through all the Thorn Lieutenant/Switcheroo/Seal Away shenanigans again. They exist, they give Raging Swordtooth pseudo-flash, and they cost a life to go through every time, so our resource-consumption still works.

We now have four of the five operations we need to make our megacombo. Do you see the end in sight?

Putting it all Together: Paladin of Atonement

We can already reconstruct what this step has to do, just from what we already know of the other operations. We need to cast a creature from our graveyard, locking Muldrotha, and then immediately use some number of Raging Swordtooth triggers to kill it, and profit 1 life. The lifegain has to be a death trigger, or we could recur it with just Slinn Voda. That’s all it takes.

Paladin of Atonement is perfect here. Assuming we can pump it by 1, we can spend a life to play it from our graveyard, then use 2 Raging Swordtooth triggers to kill it, gaining 2 life back for our down payment of just 1. Then, we can use a Slinn Voda trigger to bounce Muldrotha back, spend that life to play Raging Swordtooth, and go to town. We could play the Paladin, then bounce Muldrotha with a Slinn Voda trigger to reset the state, then replay Paladin and kill it, but doing so would use up our profit from killing it: it would cost another white mana to replay the Paladin from our hand, and we can’t avoid bouncing it when we bounce Muldrotha.

Sadly, Paladin of Atonement isn’t historic, so it doesn’t have flash. It does, however, have a converted mana cost 3 or less. Instead of spending the life to play it, we can spend it to play Teshar, Ancestor’s Apostle, and use Teshar to get back not just Paladin of Atonement, but also any merfolk we need and our Thorn Lieutenant (that’s why it will only cost 1 life to play Swordtooth now, but 2 when we were building the stack: at this level, playing Teshar is already factored into the cost). Teshar also serves as our pump mechanism: when we spend the 1 life to play him, we can play one historic spell to get back Paladin of Atonement, kill the Paladin with one Swordtooth trigger to gain a life, then cast another historic to repeat the process. Teshar only has 2 toughness, so after we gain 2 life this way, Teshar will die, and we’ll have to replay it with Muldrotha to keep going. Of course, that requires resolving a Slinn Voda trigger further down…

Now, at long last, we can put it all together. Every one of the alternating batches we put on the stack two sections ago counts as its own recursive layer. We had 2,383,743 of those, so when we’ve resolved all those triggers, we’ll wind up with 2->X->2,383,743 mana in our mana pool. X, by the way, is equal to the number of Slinn Voda triggers we still had on the stack from that first time we cast it (it feels like so long ago…), plus 2 because of an oddity of how Conway Chains work. We had 6 left, so our total is 2->8->2,383,743.

It’s worth taking a step back and remembering what that expression means. That is over two million arrows. Roughly the population of Houston, and five thousand times more than the Vintage combo.

And we are nowhere close to done.

Section 4: beating Graham’s Number

Once we’ve wrapped the last section, we’ll wind up with two million arrows worth of mana. This time, we won’t sink all that into Panharmonicon.

We spend it all making copies of Dynavolt Tower.

Then we cast an instant from our hand. Two million arrows worth of Dynavolt Towers trigger, giving us two million arrows worth of energy.

Then we spend our 2->8->2,383,743 energy to create another, much larger stack of alternating triggers. When they all resolve, we’ll wind up with 2->3->(2->8->2,383,743) mana.

In other words, by casting a single instant from our hand, we turned the 2->8->2,383,743 mana we generated before into the NUMBER OF ARROWS in the new output.

I hope you’re giggling in manic glee right now, because I sure am.

After we’ve spent all that energy, there’s nothing stopping us from doing it all over again: play another instant, generate another glut of energy, and when the dust settles, we’ll have a number where the number of arrows in it is itself a two-million-arrow expression.

Think back to the introduction of this article. That “X into X arrows” function is how Graham’s Number is defined: 64 iterations of that, starting with 3->3->4.

We started with 2->8->2,383,743, which is slightly larger than 3->3->4 (G(1)). Therefore, when we generate that many arrows, the number we’ll get will be bigger than G(2). Each time we cast an instant or sorcery, we get another iteration of our stage.

If we cast 64 instants in a row, we can beat Graham’s Number.

We will cast a lot more than that.

Doing so will take a bit of thought: even if we hadn’t already spent most of our deck slots setting up this combo, we would still only have 60 spaces in our deck, and 64 is bigger than 60. That’s where Bloodwater Entity comes in. Once we run out of Swordtooth triggers at the bottom, we can let one of our instants (Onward//Victory, say) resolve, use Teshar to bring back Bloodwater Entity (we can spend a life/energy on this, even if that gives up on some iterations of the stage, we’ll make up for it soon), use the Entity to put Onward//Victory on top, use some other resource to draw it, and replay it. We’ll get our massive glut of energy, and when all those triggers resolve Onward will still be on the stack, ready for us to use in a new, much larger iteration of the combo.

All we need to do is draw 64 cards, one at a time. Well, 63. We still have this Forsake the Worldly sitting in our hand, we might as well use it.

Section 5: And the Rest is Silence

Once we’re out of life, energy, spells in hand, everything, we don’t let everything resolve just yet. Instead, we cast the last piece of the puzzle from our graveyard: Silent Gravestone.

Silent Gravestone can tap to draw a card, at the cost of exiling itself, and can be copied as much as we want with Cogwork Assembler. That would go infinite, if not for two limiting factors: each token we make gives cards in all graveyards shroud, which means that we can’t do critical parts of our combo (like reanimating Paladin with Teshar, or tucking an instant back on top before the next draw effect resolves so we don’t deck ourselves) until every single gravestone token is gone. And, just as importantly, exiling the Gravestone is part of the effect, not the cost: if we don’t use some external force to remove all the gravestones before their abilities resolve, they will exile everything in our graveyard at the same time they draw the card.

That’s where Forsake the Worldly comes in. By casting it and copying it with Naru Meha, we can wipe out all the Gravestones, but doing so exiles them. In fact, once we’ve resolved a gravestone, we have no way of continuing without first exiling the nontoken. Our limiting factor for this layer is the number of Silent Gravestones we can cast, which will unfortunately be four. Sort of. More on that later.

This does mean we can’t let any of our critical spells land in the graveyard. Our instants and sorceries (besides Forsake, which we tucked on top at the beginning and can easily do so after it resolves later, since once it resolves all the Gravestone copies we made will be gone) can stay on the stack, under all the Gravestone activations. Slinn Voda, Paladin of Atonement, and Teshar can stay on the battlefield. Even if this costs extra energy to do, it’s worth it: we’ll get a lot more soon. The only other cards that we need out of the graveyard are our three unwind targets: Planar Bridge, Sea Legs, and Nissa, Genesis Mage. For those, we can just cast them, let them resolve, and kill them after the exile/draw trigger resolves. Planar Bridge can be legend-ruled to the graveyard for 7 mana with Cogwork Assembler and Sea Legs will fall off when the creature it’s enchanting gets bounced or killed by our combo triggers, but Nissa needs a bit more work: we have to spend 10 energy and tap two Dynavolt Towers to deal 6 damage to her. We won’t miss the lost resources: a few energy now is worth it to enable lots more later.

Brief aside: you have to feel bad for poor Nissa here. It was bad enough when we were half-summoning her billions and billions of times only to counter our own spell and leave her hanging, but now we are actually summoning her, billions and billions of times, only to immediately kill her with lightning so we can do it all again. Have you ever seen Happy Death Day? Never mind.

Where does this combo leave us? Well, we know that our first run-through of the combo got us up to 2->8->2,383,743 mana. After that, we cast a Forsake the Worldly, which gets us to 2->3->(2->8->2,383,743) (the value of the second number no longer matters and is so large it would also require a large number of arrows to express, so we’ll round down and call it 3). Each time we draw an instant and play it, we perform one more iteration of the Graham’s function, so our first draw trigger from our first Silent Gravestone will get us to 2->3->(2->3->(2->8->2,383,743)) mana, and so on.

If we feed all the mana at the end of our first iteration of the stage combo into making many copies of Silent Gravestone, we will have 2->3->(2->8->2,383,743) Separate “draw a card” triggers on the stack. We will perform a total of 2->3->(2->8->2,383,743) Consecutive iterations of our stage combo.

That number is way, way beyond what we can express with A->B->C, so it’s time to add another number to the end. Just like how up-arrow notation isn’t restricted to three arrows, Conway notation isn’t restricted to three numbers in the chain: you can have four, five, six, or more variables. For instance, the three-variable Conway chain A->B->C is equal to the chain A->B->C->1, and A->B->C->1->1, and so on.

What happens when you have a fourth number that’s more than 1? Well, think about what happens with just A->B->C. That’s the same as A^^^…^^^B, with C arrows, which we know is equal to A^^^…^^^(A^^^…^^^(A…A)), with B copies of A, and C-1 arrows between each. Therefore, A->B->C is the same as A->(A->(A->(…)->C-1)->C-1)->C-1, with B nested groups of A->(…)->C-1. Don’t worry, that’s still just a harder-to-read way of saying “A^^^….^^^B, with C arrows”.

The same thing is true with more numbers in the chain. A->B->C->2 is the same as A->B->(A->B->(A->B->(…)->1)->1)->1, which, since we can ignore the 1, becomes A->B->(A->B->(A->B->(…))), with C nested groups of A->B->(…).

In plain english, A->B->C->2 is the same as “start with A->B->*, and turn that into A->B->X, where X (the number of arrows) is equal to A->B->*. Repeat that process C times”. When the fourth number is 2, the third number corresponds to arrow multiplication, an Ackermann stage, whatever you want to call it. For instance, Graham’s Number is roughly 3->3->64->2.

For this combo, every time we cast a spell into Dynavolt Tower, we get another iteration of arrow multiplication, so if we go by the number of instants we cast, our number will be 2->3->*->2, where * is the number of times we cast something into our Dynavolt Towers.

However, after the first Silent Gravestone layer, that number will require thousands of arrows to express. After the second, it will be impossible to represent it with up-arrows at all. Fortunately, how layers interact with Conway chains doesn’t change as you add numbers: each new layer adds 1 to the last number on the chain, so our final total will be 2->X->*->3.

What do X and * represent? It might help if we expand out that chain to see what it means: 2->X->*->3 is the same as 2->X->(2->X->(2->X->(…(2->X)->2)->2)->2, where the number of times we nest a 2->X->() as the third term of the last one is equal to *. For instance, if * were 4, we’d have 2->X->(2->X->(2->X->(2->X)->2)->2)->2. We know that each time we cast Silent Gravestone, we wrap the last total we got in another 2->X->()->2, and we have 4 Silent Gravestones, which makes * equal to 5. Remember, the * also counts the lonely 2->X in the middle.

Almost. We have one other trick up our sleeve. If we counter all our instants and sorceries with Unwind, tuck them on top of our deck with Bloodwater Entity, draw them with a few spare Silent Gravestone activations, and then play our fourth Silent Gravestone but DON’T run through the combo, when The Antiquities War resolves, it will make Silent Gravestone into a creature. After that, we can make many, many noncreature copies of it, hardcast our spells again (now that it’s the main phase and the stack is clear, we can naturally play Switcheroo), put all the draw triggers on the stack, and with one Slinn Voda trigger bounce that last, animated Silent Gravestone back to our hand. Now we have another stack of draw triggers to run through, but instead of exiling a Gravestone, we’ve used up an Antiquities War trigger. We can do this precisely once, but it’s enough to pump our 5 up to 6.

X, then, represents the amount of Silent Gravestones we could make the first time we cast one. That makes our final total 2->(2->3->(2->8->2,383,743))->6->3. That number looks a bit ugly, so we can round it down to 2->3->6->3. Or 2->4->6->3. Or 2->2,147,483,647->6->3. Any number you can write down, we can use that as the second term. I’m going to use the number of layers we got from our first batch of energy, as a marker: 2->2,383,743->6->3.

Section 6: Killing our opponent

Disclaimer: card only included in the metaphorical sense.

When we’ve at long last run out of Silent Gravestones to throw, energy to spend, and triggers on the stack, we are left with nothing but a lot of mana to somehow turn into damage. We’re spoiled for choice here: Samut gives everything haste, so we can just feed all that mana into Panharmonicons, cast one last Naru Meha and have every trigger copy Onward//Victory on any creature we want, and ride that monstrosity to victory. Technically, the best option is to go through one more round with Marwyn, tap her for the maximum mana we can generate, spend it all making many Cogwork Assemblers, and swing with those, but we can’t distinguish between that strategy and any other in our total: the difference is too small.

Instead, I vote for the style win: run out a Yargle, Glutton of Urborg, shoot him with a bajillion Onward copies, and hit our opponent with the largest Frog Horror in the history of Magic: the Gathering. Our opponent has no blocks, takes 2->2,383,743->6->3 damage, and dies. Probably. Who knows, maybe they cast a really big Sanguine Sacrament or something.

Conclusion

I want to begin by saying that, despite the link at the top, this does not do more damage than the current Vintage challenger. The 408-arrow deck I’ve linked above is three years old now, and in the time since, the designers behind it have found combos that make Ackermann stages look like “mountain, bolt your face, go”.

It does, however, blow the old Vintage deck out of the water, to a degree that I don’t think anyone thought would ever be possible in Standard. If I may brag for a moment, it took six years for the magic community to crack the Ackermann puzzle. While I got a massive head-start from their efforts, I’m still patting myself on the back for managing it in four months, in a format a tenth of the size.

With that said, I believe I’ve been incredibly lucky. If I had tried this challenge in the last rotation, I doubt a combo like this would have been possible, and I think the same is true for most past Standard formats. There are simply too many moving parts, too many must-have effects that you can’t rely on having in a rotating format for this to be anything but a fluke. This isn’t just the most finite damage you can deal in Standard today, it may well be the most you can deal in any Standard, ever.

The best evidence that this deck is not the norm is how devastating the upcoming rotation will be. Cogwork Assembler and Panharmonicon, the fundamental engine that allows this deck to work, will be gone. Without them, every layer we add has to have its own built-in scaling mechanism. Not only are those few and far between, but they also usually work by generating a large amount of some resource, like mana, that you can use whenever you want. Every Ackermann stage implementation we’ve found in any format requires you to work with triggers on the stack, and carefully preserve the order in which you can do the different steps to prevent going infinite. That’s impossible with only resource pools like mana or tokens, so Graham’s Number is out of the question. In fact, my rough drafts for after rotation have struggled to get past 3 arrows.

Anyways, we’re over 11,000 words here, so I’ll leave it at that. I hope you enjoyed this deep dive into magic math and Very Big Numbers. If you want to learn more, or jump into these challenges yourself, we are currently working on the Vintage (and occasionally standard) challenge on the MTGSalvation forums here. I imagine we’ll have an updated write-up on the vintage deck some time soon.

Until then, may your combos, ogres, and onions be blessed with many layers.

I… I think my brain melted. I mean, I knew OF Graham’s number, but never had I dared that anything in magic would ever come close to that, aside from infinite stuff, you know. It’s easy to just make graham’s number of zealous conscripts with kiki jiki and smash.

This…. It’s a work of art.