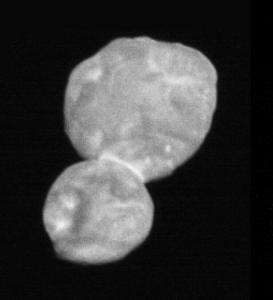

A few days ago, the world was introduced to this photo:

This weird snowman-shaped thing is the most distant place humanity has ever explored.

Its name is Ultima Thule. It was flown by and photographed by the New Horizons probe, which famously got us our first look at Pluto back in 2015. Over the next few years, as scientists closely examine the data it’s transmitting, we will gain a far greater understanding of how our solar system formed and what it looked like five billion years ago. Its value will be immeasurable.

I’m not here to talk about that. Some day, when we’ve actually learned those things and don’t just have initial photographs, I might. In the meantime, I want to talk about something more innocuous: its name.

There’s a lot of politics involved in the naming of astronomical objects. While scientific literature uses certain rules to convey the most important information (Kepler 22b for instance, indicates the first planet orbiting the star Kepler 22), just try asking a fifth grader to remember the name 2014 MU69. The names of the planets have stuck around since antiquity, but what about the new ones we discover? Even within our solar system, new dwarf planets get found in the Kuiper belt (where Pluto is, basically) every year. Should we name them all after Roman gods? What happens when we run out? And why are we still using names from a mythology revered only in western civilization?

Scientists have fixed the last two problems by expanding to new mythologies. Sedna, for instance, is named for the Inuit goddess of the sea. Smaller objects, asteroids and comets like Ultima Thule, are named for meaningful phrases or minor heroes in any number of languages and mythologies. But even that can be fraught. The scientists who named Ultima Thule have since come under fire for using the phrase, which has connections to Nazi ideology. To be clear, NASA didn’t intend that meaning. So why did they pick it?

Ultima Thule is originally latin, and translates to “beyond the farthest land”. Except that it isn’t. “Ultima” from the Late Latin “ultimare”, or “to come to an end”, is, but “thule” is not a word. It comes from Ancient Greek, where it is also not a word. Anecdotally, it looks Germanic. Mixtures of Latin and Germanic words aren’t uncommon in English, but the phrase “ultima thule” predates English.

To understand where the word came from, we have to go back 2000 years, to a man named Pytheas of Massalia. He was a Greek geographer who lived from around 350 to 240 BCE, hailing from a colony that would later become Marseille, France. During his lifetime, he explored the north of Europe in a voyage he later described in his work, “On the Water”.

Sadly, this manuscript has been lost to time. All we have of it are the excerpts quoted by other, later authors. But from those, we can begin to uncover his route.

His first hurdle would have been the Strait of Gibraltar, the narrow passage connecting the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean. At the time, the rival nation of Carthage had closed the Strait to all ships from other nations. Historians have speculated that he began his voyage overland, journeying to the mouth of the Loire and constructing his ship there. However, it is more likely that he went through the Strait, either by running the Carthaginian blockade or by negotiating for safe passage.

From there, he travelled to Britain, likely the first Greek ever to do so (while there are older Greek artifacts in archaeological digs in the UK, it’s believed those were indirectly brought there by traders). There, he circumnavigated the British Isles, mapping the coastline and making first contact with the people there. This is where the name “Britain” comes from: it’s a transliteration of a Celtic word roughly meaning “land of the painted men”, referring to the Celtic tradition of painting their faces.

He discovered the Orkney Islands, to the north. He sailed to the Vistula River in the north of Poland, and the entire Germanic coast of the Baltic Sea, what today is Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. He is the first explorer of his people to encounter drifting sea ice. And he discovered a distant land called “Thule”.

By Pytheas’s account, Thule is an island six days’ travel north of Britain. That would put it on the coast of Norway, or possibly Iceland. It was inside the arctic circle: Pliny the Elder reported that it as having no night on the summer solstice, a phenomenon known in principle to the Greeks but never before seen in person. The people there lived on roots and grain, and it is likely their language gave him the name “Thule”.

From there, he sailed northward, but discovered nothing but frozen ocean and was forced to turn back before long. When he returned, the annals of his journeys became the Greeks’ best source of knowledge on these distant lands.

And of those lands the most distant of all was Thule.

This, then, was the source of the word, and of its mysticism: before Kepler, before Magellan, before even Rome, Thule was the last name on the map. Beyond it be dragons.

So far, this story is an tale of exploration and etymology that began and ended thousands of years ago. Where do the Nazis come in?

Today, discussion of Nazism as an ideology and ethos fixates on its genocidal xenophobia and antisemitism, but there was far more to Hitler’s platform than “kill the Jews”. And the other stuff was weird. Among Nazism’s early influences was an esoteric philosophy called “Ariosophy“. It mixed social Darwinist racial theory over the Aryan race and bizarre mysticism, even giving the movement the symbol of the Swastika. This evolved into a widespread obsession with the occult in the highest circles of Nazi Germany, particularly in the SS. According to Eric Kurlander, a professor at Stetson University, various members of the Nazi leadership believed in everything from Satanism to the claim that the Aryan race descended from the space aliens who built Atlantis. The iconography of the SS, with its skull rings and runic logo, were built on Heinrich Himmler’s fascination with witchcraft and esoteric traditions. He even commandeered a medieval castle and remodeled it to be reminiscent of the Arthurian Grail legend. My personal favorite, however is the idea that the Aryan Race descended from superbeings that evolved from the inhabitants of icy moons that impacted Earth in antiquity like some antisemitic Kal-El, a viewpoint Hitler supported well into 1942.

From Ariosophy and the swamp of mysticism that abetted it came a group called the Thule Society. It was founded in 1918, and centered around the belief that the Aryan Race traced its origin in antiquity to the Hyperborean people, who in turn came from the island of Thule. Each new recruit had to take this pledge:

“The signer hereby swears to the best of his knowledge and belief that no Jewish or coloured blood flows in either his or in his wife’s veins, and that among their ancestors are no members of the coloured races.”

The society didn’t last long: while it’s hard to trace the actions of secret societies, it appears to have been forgotten about by the early 1920s. But late in 1918, a journalist and Thule Society member Karl Harrer persuaded his friend Anton Drexler to form the activist group Politischer Arbeiter-Zirkel, the “Political Workers’ Circle”. In January of the next year, its members decided to create a new party, the German Workers’ Party. A few months later, a young man named Adolf Hitler began attending meetings.

A year after that, the German Workers’ Party had been dissolved, replaced by the Nazi Party that would later kill a third of all Jews in existence.

There is little evidence that the Thule Society itself had any influence on Nazism: the only person involved in that story to actually be a member, Harrer, resigned the party in protest in 1920. True, it was antisemitic, but so was most of Germany at the time. Yet its role in the origins of the great evil of the 20th century has left it inextricably linked with that organization.

Which brings us back to Ultima Thule. The name does not refer to the Nazi’s use. In fact, the Thule Society was far more preoccupied with the island itself than with the ancient phrase for “beyond the known world”. Yet its members, and by extension its beliefs, did play a part in the early origins of Nazism.

On balance, I don’t think it matters. Even if you accept the counterfactual argument that Nazism would not exist without the Thule Society’s input, they are a footnote in the story of that ideology. It was merely a part of the same mystic tradition in Weimar Germany that played a role in Hitler’s rise and the iconography of his movement. So was Thor, for that matter, and we still watch The Avengers.

As I write this, “Ultima Thule” delivers 125,000,000 search results on Google. “Ultima Thule nazi” has roughly 1% as many. Whatever its connotations may have been in the past, the phrase has returned to harmony with its meaning from antiquity. It stands for exploration, for humanity’s innate desire to fill in the blank spaces on the map. It stands for the work of hundreds of scientists to build a machine that could fly 6.5 billion kilometers through the vacuum of space to fly by an object even our most powerful telescopes on Earth couldn’t see and take pictures. It invites you to wonder, if 2000 years ago the name referred to Scandinavia and today it belongs to the most distant reaches of our solar system, where Ultima Thule will be 2000 years from now.

Place your bets now.